Maps without journeys: the practice of armchair travel

The third, and possibly the last, in a series on maps

‘There is a certain madness comes over one at the mere sight of a good map.’

Freya Stark, Letters from Syria (1943)

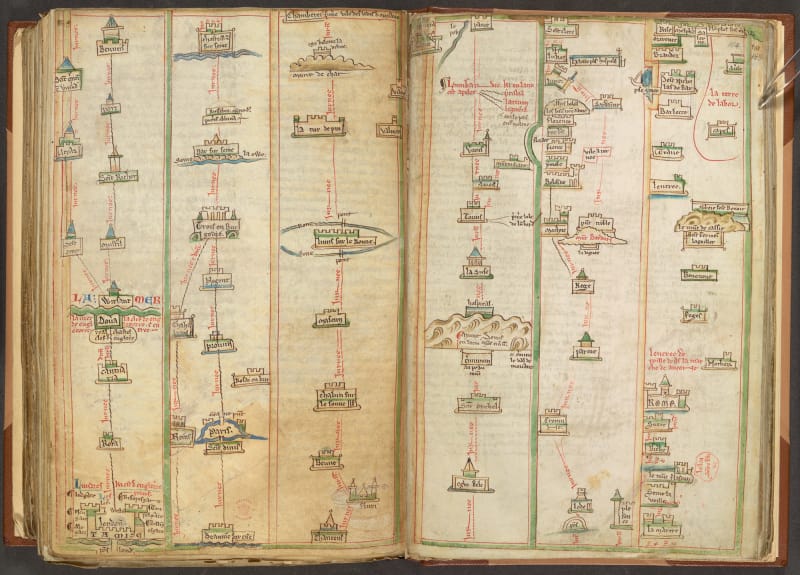

The thirteenth century English monk Matthew Paris—historian, translator, artist, cartographer and minor international envoy—produced a series of beautifully illustrated itinerary maps, covering pilgrimage routes from England to Rome and onward to the Holy Land. They aren’t altogether unlike the kind of guidebook you might pick up today for a popular long-distance walking trail: rather than trying to map out the whole vast area between the start and the destination, Paris’s itineraries confine themselves to the specific route in question; they give appropriate stopping points and the distances between them, and even have fold-out leaves providing helpful information about the amenities available along the way.

Unlike modern guidebooks, though, they’re not intended to be tucked in a rucksack and taken out on the trail. In fact, quite the opposite: they seem to have been produced for people who had no intention at all of going on the physical journey depicted. A reader—a monk, like Matthew, safely tucked away in the cloisters of St Albans Abbey—could instead use his itineraries to guide a kind of virtual pilgrimage, visualising the stages along the route as well as the eventual destination, as an aid to prayer and contemplation. They’re spiritual maps, for armchair travellers.

I’ve been on imaginary journeys of my own: planning big, ambitious trips I’ll never take, or retracing old routes in the imagination to get myself to sleep. But I've never made it as far as Jerusalem, stopping to pray at appropriate points along the way. For me, and I suspect for many of us, armchair travel tends to be a fairly aimless, occasional pastime, without anything like the focus or deliberate intent of the virtual pilgrimage: but if we’re going to do it at all, perhaps we ought to try to do it properly.

One possible contemporary guide is Judith Schalansky, a modern adept in the discipline, whose Atlas of Remote Islands represents a lifelong fascination with exploring far-flung places through maps and stories without ever attempting to visit them. The subtitle, Fifty Islands I Have Never Set Foot On, and Never Will, has the unfortunate ring of a throwaway listicle, a bit of online clickbait: but inside is a beautiful, thoughtful book. The introductory essay draws on Schalansky’s memories of childhood in East Berlin: in the libraries and schoolrooms of a republic whose citizens were forbidden to travel, her fingertips used to trace the outlines of distant archipelagos on the pages of atlases, letting names and coastlines lodge in her mind in the knowledge that, for her, they would always remain in the realm of the imagination. And that is where she has kept them: her islands are still places of story, myth and wild rumour, isolated stages on which scenes of melodrama and baroque villainy have played out over many centuries.

“Paradise is an island,” she writes. “So is hell.” From storm-battered rocks to coral atolls, the islands on her list have been settings for murder, mutiny, starvation, rape and infanticide. There are mysterious disappearances, doomed utopian experiments and millennarian cults; there are rumours of cannibalism, ants that hunt crabs, a man devoured by a vast horde of penguins. At the end of each story, there is a note of futility, isolation, nothing left but the endless sound of the waves breaking on the shore.

Schalansky approaches her islands as an artist rather than a geographer or a historian: she makes the case for maps as a form of literature, and for her, the things that might have happened, or that are said to have happened, are of more interest than a reductive quest to find out what actually ‘did’ happen. As for the islands themselves, all are present in the book as exquisite, hand-drawn maps, but there are no other photographs or illustrations to get between the reader and the imagination. The crux of her project is the relationship between the map and the place we envisage when we look at the map, and nothing must be allowed to break the spell.

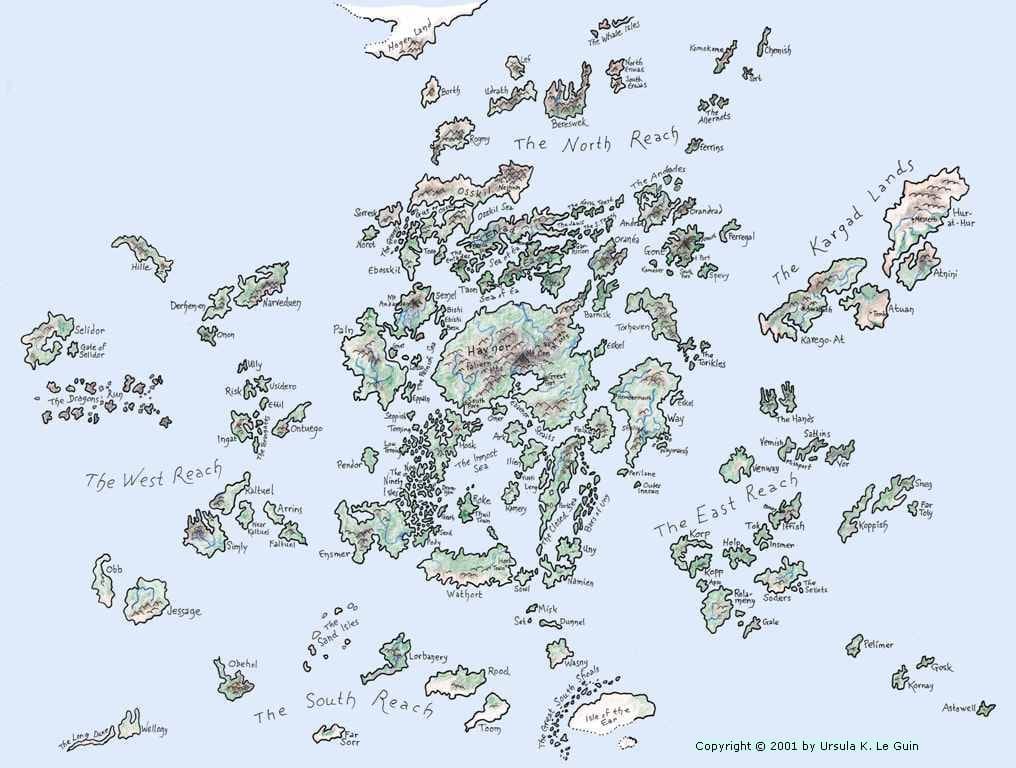

Of course, the perfect unvisitable land is one that doesn’t exist at all: and there are plenty of maps of these to be found. If you escape to an imaginary world—Tolkien’s Middle Earth, George R. R. Martin’s Westeros, Ursula K. Le Guin’s Earthsea, and a thousand other fantasy creations besides—most authors are generous enough to supply a map: often a spidery pen-and-ink creation complete with battlemented towns, sawtoothed mountain ranges, redundant compass roses, and ye olde illustrationes of ships and sea monsters. You might reasonably assume that these are afterthoughts, provided just to help the reader keep track of the positions of various made-up places as the heroes progress through their inevitable transcontinental quests: but very often, it seems, the map often occupies an earlier and more pivotal role in the world-building process.

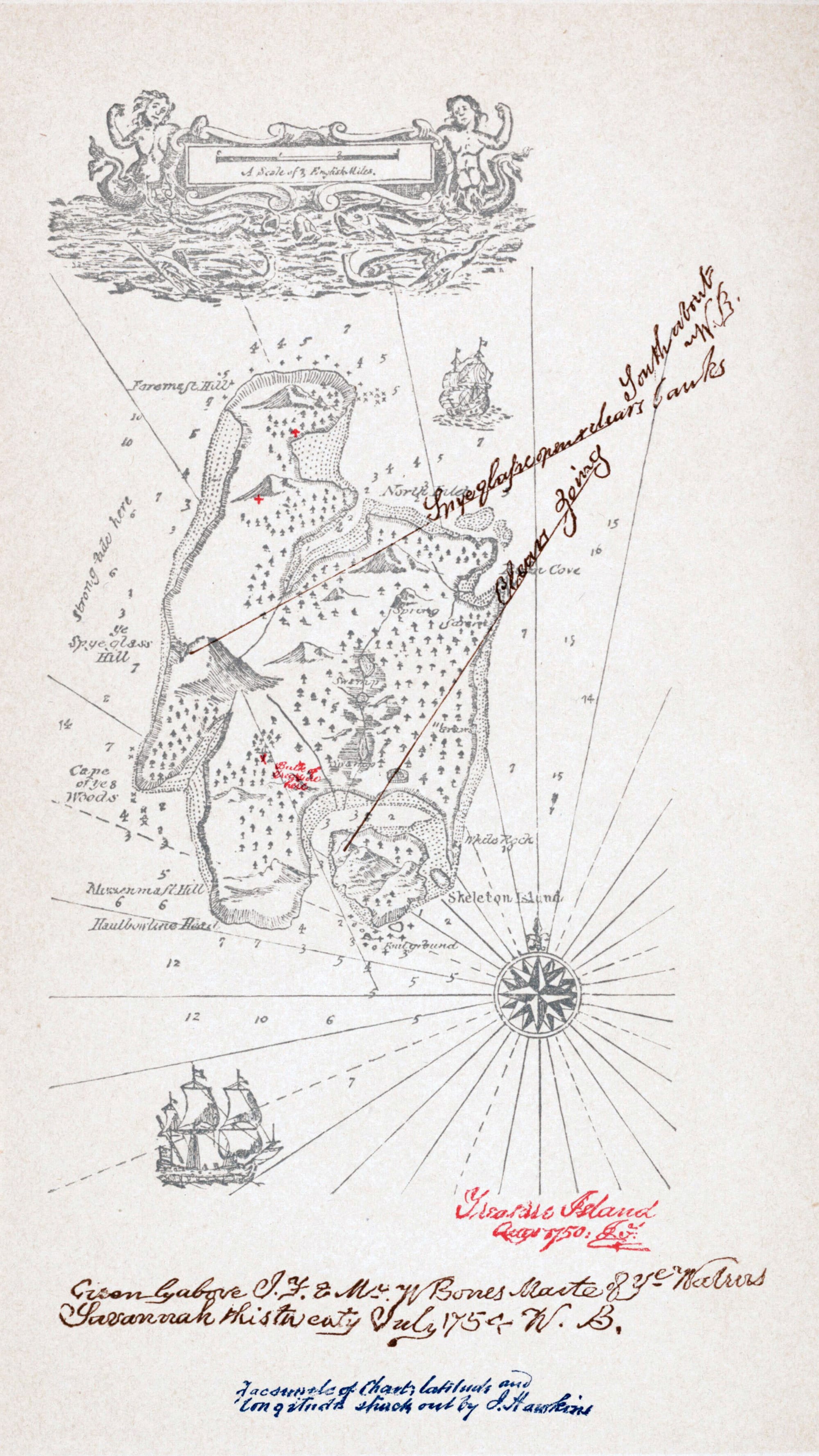

Spare a thought for poor Robert Louis Stevenson, who sketched the original map for Treasure Island with no more thought than a doodle, and used its geography as the starting point for the action in his famous adventure. He then sent in the manuscript to his publisher:

The proofs came, they were corrected, but I heard nothing of the map. I wrote and asked; was told it had never been received, and sat aghast. It is one thing to draw a map at random, set a scale in one corner of it at a venture, and write up a story to the measurements. It is quite another to have to examine a whole book, make an inventory of all the allusions contained in it, and with a pair of compasses, painfully design a map to suit the data. I did it; and the map was drawn again in my father’s office, with embellishments of blowing whales and sailing ships, and my father himself brought into service a knack he had of various writing, and elaborately FORGED the signature of Captain Flint, and the sailing directions of Billy Bones. But somehow it was never Treasure Island to me.

The proportions of Stevenson’s island were all arbitrary, because it was just the setting for a good yarn, but at least he’d started with a map, and fitted the action to it: reproducing it faithfully was laborious, but he knew it was possible.

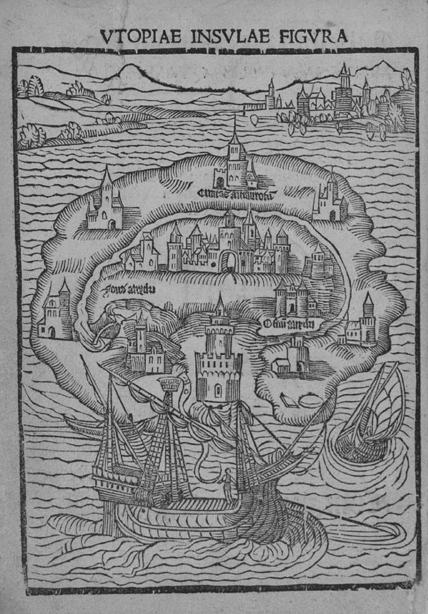

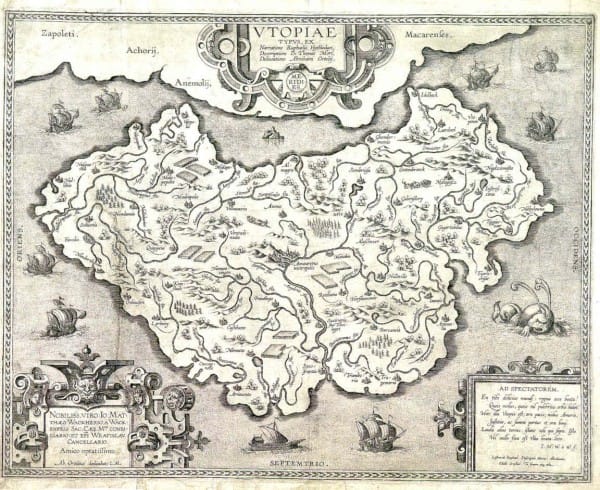

Not so Sir Thomas More: he gave precise dimensions for the topography of his own invented island, but cartographers have not found them easy to follow.

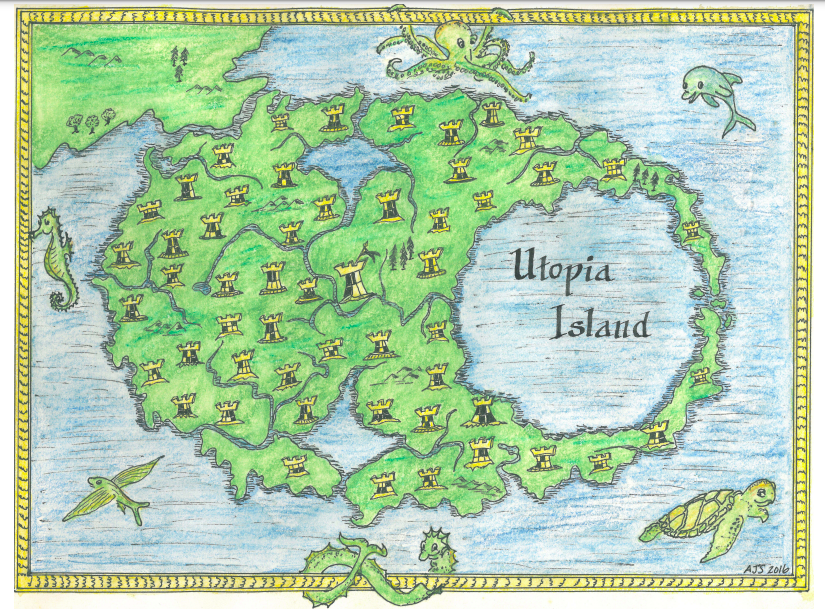

Utopia, he says, is shaped like a crescent, two hundred miles broad, with a big central bay five hundred miles around, whose mouth is only eleven miles wide; a central river, running through the capital, is a hundred and forty miles long, and the island is separated from the mainland by a channel fifteen miles wide. The original 1516 edition has a woodcut illustration of the island, but the river appears to be too long and the crescent shape seems somewhat dubious. Later attempts, including those by such illustrious real-world cartographers as Abraham Ortelius (creator of the Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, often billed as the first modern atlas) have diverged even further from More’s specifications. Scholars of More had despaired of finding a solution that satisfied all the conditions laid out in the text: an appropriate conclusion, perhaps, for this imaginary land, but mathematicians are not known for cheerfully leaving problems to remain beautifully unsolved: witness this 2016 paper from a professor at a Tennessee liberal arts college, who has come up with algorithms to satisfy the original description in full. To give him his due, he at least had the grace to include some sea monsters.

Utopia as pictured in the original 1516 edition, mapped by Abraham Ortelius in 1595, and reinterpreted by Prof Andrew Simoson in 2016

More’s island is of course a moral and philosophical experiment, not just a source of entertainment, and its dimensions, which hint at an idealised, symmetrical version of Great Britain, reflect the geographical conditions that he believed would favour the creation of the perfect state. In fact, though, in every fantasy novel I’ve ever read, there is always a ‘moral geography’ of some kind; the map is always loaded with social and political meaning. The trashier the novel, the more explicit is the map of good and bad: the same tropes come up in countless twentieth-century fantasy books, mainly written by English-speaking white men. Northerners are hardy, honest types with bland food, simple clothes and big swords. There are rich and populous nations in the south and east, but their inhabitants are decadent and sneaky; they don’t fight fair and will try to poison you. Desert lands have cod-Arabic names like Zakh’ad and al-Jakkan, and their nomadic inhabitants are ferocious warriors who will die rather than face dishonour: they’re initially hostile but they will probably end up fighting the bad guys on your behalf. Just offshore there’s typically an archipelago ruled by very independent-minded lords; its barren islands have a minuscule population, no obvious source of timber, and (somehow) hundreds of powerful warships. Far away to the west, over the sea, there’s rumoured to be a mysterious land that sounds a bit like heaven.

Of course, these tropes have long been criticised, and plenty of writers have tried to avoid them or to subvert them in various ways, but they’re surprisingly hard to escape altogether: you can substitute different political views and different prejudices, but the imaginary map remains a kind of Rorschach inkblot test for an author’s worldview. Even when the fictional world maps directly onto our ‘real’ one (as in the Harry Potter universe, or Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials series) the same stereotypes generally apply. The determining role of geography has long been a bone of contention in history: in speculative fiction, it seems to be more or less taken for granted.

It’s not just fantasy novels, though. The attempt (conscious or otherwise) to reflect the moral order and the spiritual world on the map is a practice as old as cartography itself. I mentioned earlier in this essay series that the Egyptian afterlife appears to be the subject of some of the oldest maps of all: and actually, the idea that spiritual and physical geographies should be separate is a relative novelty. In the days before supposedly accurate and comprehensive world maps, it was perfectly natural to assume, perhaps in a slightly hazy way, that the afterlife (if there was one) happened in real places with identifiable (though inaccessible) physical locations.

When Odysseus wants to talk with the dead Tiresias, he doesn’t pop up to Circe’s attic with a ouija board: he travels to a real place in a real ship, its sails filled by the North Wind, even if he has to fill a trench with ram's blood on arrival in order to secure an interview with his man. Later inhabitants of the Mediterranean located the Fortunate Isles, abode of the divinely favoured dead, somewhere out in the Atlantic, and they seem to have been identified with either the Canary Islands or with Madeira. At one point the rulers of Carthage apparently became so worried about a mass exodus of their citizens to Madeira that they imposed the death penalty on anyone attempting to travel there, and massacred the colonists who had already arrived. (A reminder of Schalansky’s dictum: “Paradise is an island. So is hell.”)

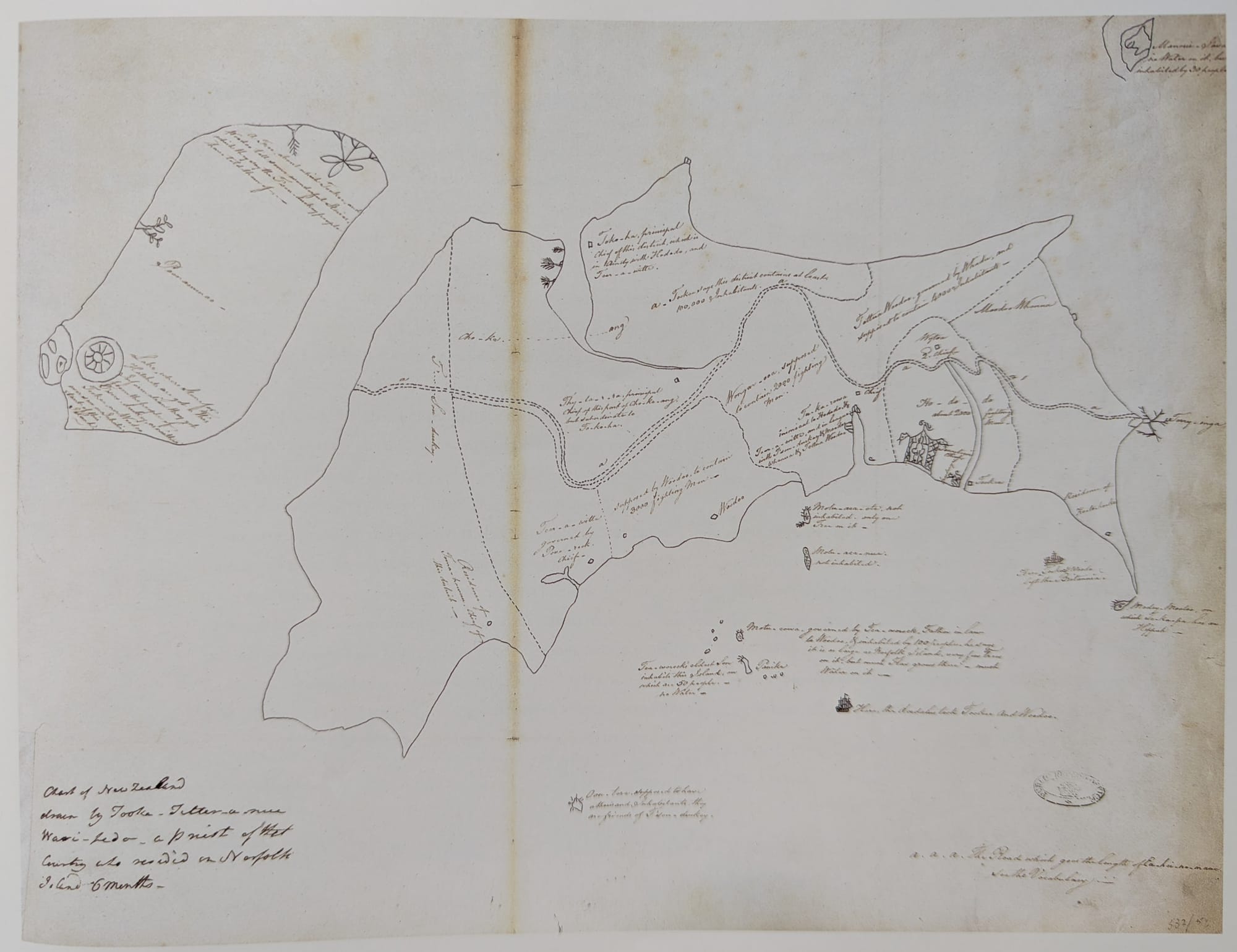

Several reproductions exist of a map of New Zealand drawn by Tuki Tahua, a young Maori, after he was kidnapped by a British official in 1793 in the vain hope that he would be able to teach convicts at the penal colony on Norfolk Island how to dress flax. (He couldn’t. He was a man of high status, and flax was women’s work. But he stayed with the British for six months, and copies of his map were circulated afterwards as (surprising) evidence of the natives’ intelligence and sophistication.) On it, physical and spiritual geography coexist comfortably: the coastline is detailed, settlements and natural resources are depicted, as is the path followed by the spirits of the dead as they journey to their final point of departure at Te Rēinga.

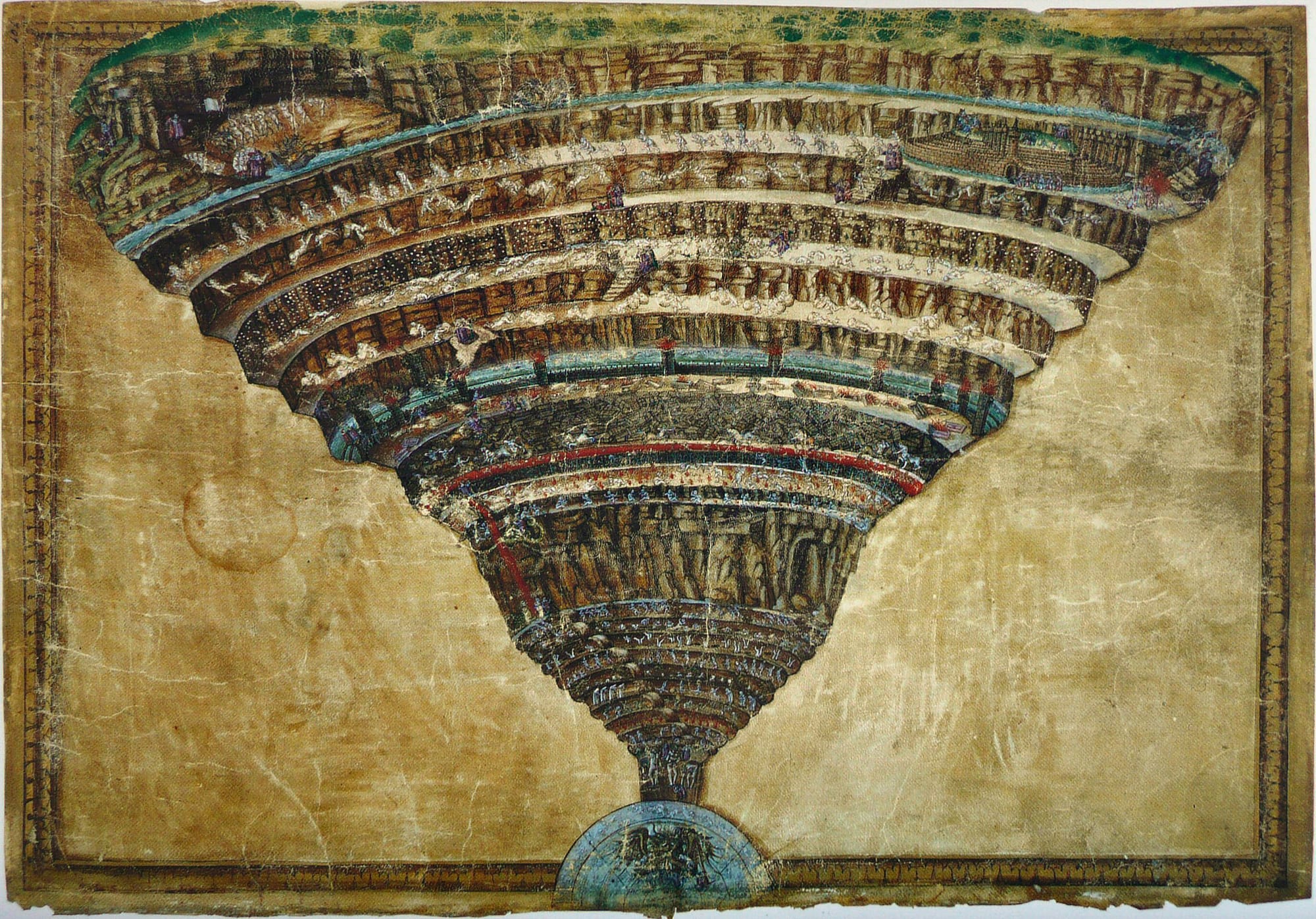

Not only can the route to the afterlife be located on a map: with some ingenuity, heaven and hell can themselves be mapped. As with More’s Utopia, all that’s needed is a precise topographical description: and for this, Christians can look to Dante. His Divine Comedy is a journey through a concrete reality, a landscape whose features are enumerated and described one by one, with clues as to how the elements are positioned relative to each other, and to where they are located on (or in, or above) the Earth.

But detail and precision don’t always mean clarity, particularly when translating someone else’s account of a journey into a well-defined mental image, or indeed into the supposedly objective format of a map or diagram. When confronted with a plethora of concentric rings, ditches, and the walls of Dis, a casual reader of Dante’s Inferno is likely to be just as grateful for a visual aid as someone trying to follow a Hobbit’s route from the Shire to Mordor. Fortunately, some of the finest minds of the Renaissance were happy to help: from Botticelli’s ‘Map of Hell’ and the detailed schematics of the Flemish artist Stradanus, to Galileo Galilei’s 1588 lectures in which he sought to adjudicate between the differing constructions and dimensions proposed by the Florentine mathematician Antonio Manetti and the Lucchese scholar Alessandro Vellutello.

If the seriousness of these efforts prompts a question about whether Dante’s readers in succeeding centuries believed literally in the structure of his Inferno, it’s worth remembering that the paradise of the Divine Comedy proceeds outward in concentric spheres around the Earth, following the geocentric model that Galileo is well known for rejecting. We needn’t assume that he, and all other Renaissance readers, held a straightforward belief in the concrete presence of a vast conical pit beneath the earth, centred on Jerusalem, with its edges stretching from Marseille to the Indus Valley, and from the Baltic to the southern Sahara. Taking something seriously isn’t the same as holding it to be true. (It might not be advisable to keep on comparing Dante with Tolkien, but equally serious cartographic firepower has been brought to bear on Middle Earth, complete with learned disquisitions on the likely geology of its various mountain ranges: see, for example, Karen Wynn Fonstad’s Atlas of Middle-Earth, widely welcomed by her fellow Tolkien scholars as both ‘accurate’ and ‘authoritative’.)

Perhaps ‘did they literally believe it?’ is the wrong question anyway. As the theologian N. T. Wright points out in a discussion of the truth of the Gospels, the question of whether a work of ‘literature’ is ‘literally’ true suggests a degree of confusion about how we relate to the truth of what we read. The stark, binary assertion that something must either be real or not real belongs to an Enlightenment world of Newtonian physics and of maps with no blanks left on them, a world in which we expect everything to be clearly describable and the line between truth and falsehood to be sharp. But Dante was writing not long after Matthew Paris made his pilgrim’s itinerary and his beautiful but undeniably funny-looking maps of Britain: at a time when the few world maps produced by European Christians were centred on Jerusalem, and when their fringes belonged firmly to the ‘here be dragons’ tradition of European cartography. Even in Galileo’s day a vast, unknown continent was still depicted spanning the southern hemisphere beyond the Strait of Magellan, its weight required to balance the northern landmasses of Eurasia and North America. Did they all ‘literally’ believe in the vast terraced mountain of Purgatory rising out of the Pacific Ocean at the point on the Earth’s surface directly opposite Jerusalem, a thousand miles south of Tahiti? Maybe not: but then, they didn’t believe in Tahiti either, because no European had yet been there. It’s not that people in antiquity, or in the Renaissance, were incapable of distinguishing between fable and reality—they were perfectly capable of doing so, and of arguing over the distinction vociferously. But with so much still unknown, and with a prudent acceptance that it would remain unknown, I don’t think they necessarily always felt the need to draw such sharp lines between them.

It is different for us: we have chased all the dragons off our maps. Captain Cook sailed the high latitudes of the southern ocean, looking for a vast Terra Incognita, and found mostly ice—and now the ice, too, is melting. So perhaps it’s inevitable that we retreat to mapping Middle Earth instead: or, to take the more recent examples of J. K. Rowling and Philip Pullman, we locate our fantasy worlds hidden in plain sight, underneath the tracing paper layer of our own flimsy reality.

In this predicament, Schalansky’s Atlas of Remote Islands, filled though it is with stories of human suffering, becomes somewhat heartening. She recognises that map-making is a colonial venture, that to chart a place is always, in some way, to claim it. Yet her wild travellers’ tales and Gothic mysteries also serve to reverse that process: to remind us that no amount of hydrographical surveying can truly conquer these islands, or the seas that surround them. A map suggests possibilities, and the possibilities are always far greater than the map suggests. No official nautical chart can capture the whole truth. She writes:

An island offers a stage: everything that happens on it is practically forced to turn into a story, into a chamber piece in the middle of nowhere, into the stuff of literature. What is unique about these tales is that fact and fiction can no longer be separated: fact is fictionalized and fiction is turned to fact.

That’s why the question whether these stories are ‘true’ is misleading. All text in the book is based on extensive research and every detail stems from factual sources. I have not invented anything. However, I was the discoverer of the sources, researching them through ancient and rare books, and I have transformed the texts and appropriated them as sailors appropriate the lands they discover.

The interaction with a map ceases to be merely transactional, and becomes once again something deeply personal, something creative, just as it was for the mediaeval cartographers. Schalansky certainly knows the madness that Freya Stark experienced at the sight of a good map. For her, these are objects of desire, not of data: ‘Anyone who opens an atlas,’ she says, ‘wants everything at once, without limits—the whole world.’ She tells of the erotic charge that she felt, running her fingers over a relief globe in the Berlin National Library, the peaks of the Himalaya and the groove of the Mariana Trench: not quite as wholesome as Matthew Paris’s virtual pilgrimage, but she’s probably having more fun. And in the stories she tells, themselves suspended in that seductive territory between history and fable, there are monsters and dragons still.

Sources

Mick Ashworth (ed.), The Times History of the World in Maps (HarperCollins 2014)

Brown University Library, Infernal Geometry

Anika Burgess, 'Mapping Dante's Inferno, One Circle of Hell at a Time', Atlas Obscura, July 2017

Daniel K. Connolly, 'Imagined Pilgrimage in the Itinerary Maps of Matthew Paris', The Art Bulletin, Vol. 81, No. 4 (Dec., 1999), pp. 598-622

Karen Wynn Fonstad, Atlas of Middle-Earth (HarperCollins 1994)

Homer, Odyssey Book X

Walter Woodburn Hyde, Ancient Greek Mariners (OUP 1947)

Rose Mitchell and Andrew Janes, Maps: their untold stories (National Archives / Bloomsbury 2014)

Thomas More, Utopia, Book II

Judith Schalansky, Pocket Atlas of Remote Islands (translated from the German by Christine Lo, Penguin 2011)

Andrew Simoson, 'The Size and Shape of Utopia', Bridges Finland Conference Proceedings 2016, online

N.T. Wright, The Resurrection of the Son of God (Fortress, 2003)

Links above are either to online sources, or they’re affiliate links to Bookshop.org, where I receive a 10% commission on sales, with another 10% going to support independent bookshops.

Image credits

Matthew Paris itinerary map: British Library Board, licensed by Creative Commons. Ko Chueak: author photograph. Treasure Island: Robert Louis Stevenson, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. 1516 Map of Utopia: public domain via https://theopenutopia.org/. 1595 Ortelius Map of Utopia: public domain via Wikimedia Commons. 2016 Map of Utopia: Copyright Andrew Simoson, quoted from 'The Size and Shape of Utopia' (fair use). Earthsea: copyright Ursula Le Guin, available under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. Tuki Tahua map: reproduced with permission from Mitchell and Janes 2014. Botticelli's Map of Hell: public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Hereford Mappa Mundi: public domain via Wikimedia Commons.